From Stockholm and Brussels to Vienna: a multidisciplinary team co-developed a strategy to reach ambitious energy targets in three Viennese districts

In mid-September, a Stockholm and Brussels’ delegation of experts from the interdisciplinary team of the Cities4PEDs project visited the City of Vienna. Their mission: to test the methodology for the development of Positive Energy Districts (PED) in three Viennese districts. Through this exercise the cities shared their experiences resulting from the 2 years research and tools tested in their own hometowns. The ultimate goal is to synthesize the findings and considerations in a resource that would help other cities working on district transformations with ambitious energy targets.

The task was not that easy. First of all, the experts had to get better understanding of the Vienna city administration. Out of 70 departments, some 20 deal with urban development, city planning, city zoning, energy and climate and other services relevant to Positive Energy Districts. These work closely with urban renewal programs like WieNeu+ and external public agencies such as Urban Innovation Vienna (UIV) to make Vienna climate neutral and more livable.

Then came the districts themselves: new brownfield development areas and existing district transformation. Each of them is very different one from another. One of the example districts has a rather young population with a large share of people with migrant backgrounds. About 54% of the population has no or only partial voting right. Heat islands, threatening mainly elderly, have been identified. The area consists mainly of residential and privately owned buildings as well as social housing, with a main shopping street and few commercial and industrial buildings in between. The existing but fragmented district heating network has potential for densification.

How to make the district a positive energy district? Where did the City of Vienna start?

What if this district was to become a Positive Energy District? Florian B Stiller from the Technical Urban Renewal Department of the City of Vienna thinks about the question for a couple of seconds and says: “In fact, districts do not have yet an action plan for a long-term transformation process. To get started with pilot districts, the city launched the WieNeu+ program. It is responsible for identifying and implementing smaller pilot projects in a 3-year phase per district. These ‘quick wins’ are easily replicable and contribute to the Smart Climate City goals of the City of Vienna.” The pilot projects include, for example, refurbishment of residential buildings whose residents are already interested and engaged in energy transition, setting up of citizens’ energy communities, ‘positive energy streets’ connected to extended district heating network or green buildings measures tackling heat islands.

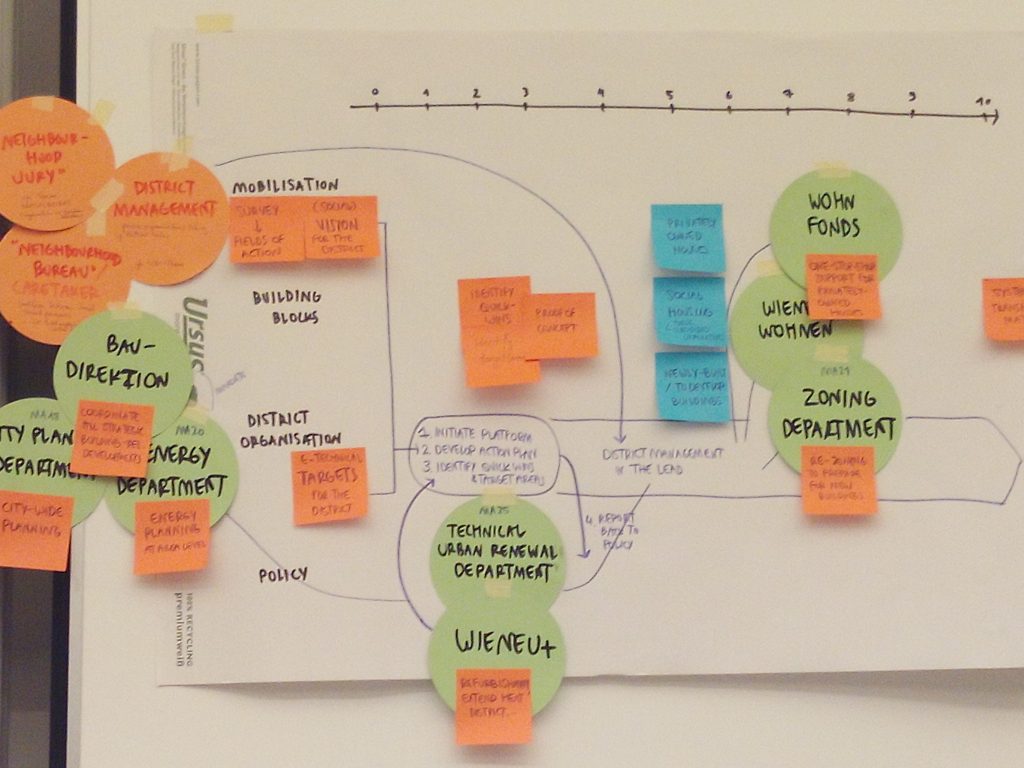

The team believes that to achieve a transformative change, the city administration and district-based organizations have to join their forces.

On the one hand, the City of Vienna has to make its objective of becoming climate-neutral by 2040 more tangible e.g. in technical plans on district level. Questions like “Do all districts have the same targets or should some of them be higher because of their higher energy-saving potential and different potentials for renewable energy production?,” “Where does the city set priorities?,” “Which technical measures are the most appropriate for each district?” have to be answered in order to achieve the goal.

On the other hand, district-based organisations (for example social centres and caretakers) which benefit from the citizens’ trust, should be leading the process of analysing and engaging citizens in the creation of a common vision for the district. This would reflect citizens’ aspirations, needs and worries concerning their living space (not only energy and climate issues!). Such co-created vision would also help preserving the cultural and social identity of each district, thus enhancing citizens’ engagement and the feeling of ownership. This so called ‘social reading’ would then be confronted with the ‘technical plan’ within a permanent platform involving the city and district-level elected representatives, staff, district-based organisations and citizens. Together, they would set and monitor the priorities, specific measures to be implemented and the timeline.

The city of Vienna is largely dependent on gas which covers 41% of the city’s heat supply. Existing projects, such as the building refurbishment with integrated renewable energy production in Geblergasse or a brand-new low energy district Aspern Seestadt, prove that technical solutions are available on the market.

Today, the biggest challenge seems to be the transformation of the city administration whose structure derives from over 100 years ago, and its relations with politicians, local stakeholders and citizens. They have to find new ways to face together one of the biggest challenges of the 21st century.

The three cities are now working on valorizing their experiences and share specific tools and considerations that would help other cities to ask themselves the right questions and find solutions for ambitious district development in terms of energy. This was made possible thanks to the Cities4PEDS project financed by JPI Urban Europe programme.

The post From Stockholm and Brussels to Vienna: a multidisciplinary team co-developed a strategy to reach ambitious energy targets in three Viennese districts appeared first on Energy Cities.

Fuente: ENERGY CITIES

Enlace a la noticia: From Stockholm and Brussels to Vienna: a multidisciplinary team co-developed a strategy to reach ambitious energy targets in three Viennese districts